Imagine Goldman Sachs was partly owned by a government-controlled conglomerate. Now imagine authorities were investigating one of its leaders. That is effectively what is happening in China, where the president of CITIC Securities faces an insider trading probe. The latest regulatory assault on China’s biggest brokerage is just one of several headaches facing the industry.

The accusations against Cheng Boming and two senior colleagues are vague. What is clear is that the official backlash against China’s brokerage industry, which coincided with the country’s stock market slump, is still in full swing. Four CITIC Securities executives confessed to insider trading last month. Last week, the regulator fined four brokerages $28 million for failing to check clients’ identities.

It’s a stark contrast with the first half of the year, when brokerages were at the vanguard of the frenzy in Shanghai and Shenzhen. As valuations soared, securities firms raised almost $20 billion in equity from investors in Hong Kong and on the mainland.

Now that capital is being used in a futile attempt to prop up the market. In July, leading brokerages pledged to invest 15 percent of their net assets – then worth around $19 billion - and not sell until the Shanghai Composite Index reached 4,500. Some have pumped a fifth of their net worth into equities. With the benchmark hovering around 3,000, brokers are nursing hefty losses.

Meanwhile, business is waning. Daily trading volumes on China’s two main exchanges have halved since early June, while margin lending balances – a lucrative source of business - have roughly halved, to little more than 1 trillion yuan. Plans to introduce so-called “circuit breakers” to limit wild swings in the market will further crimp activity. Initial public offerings have dried up.

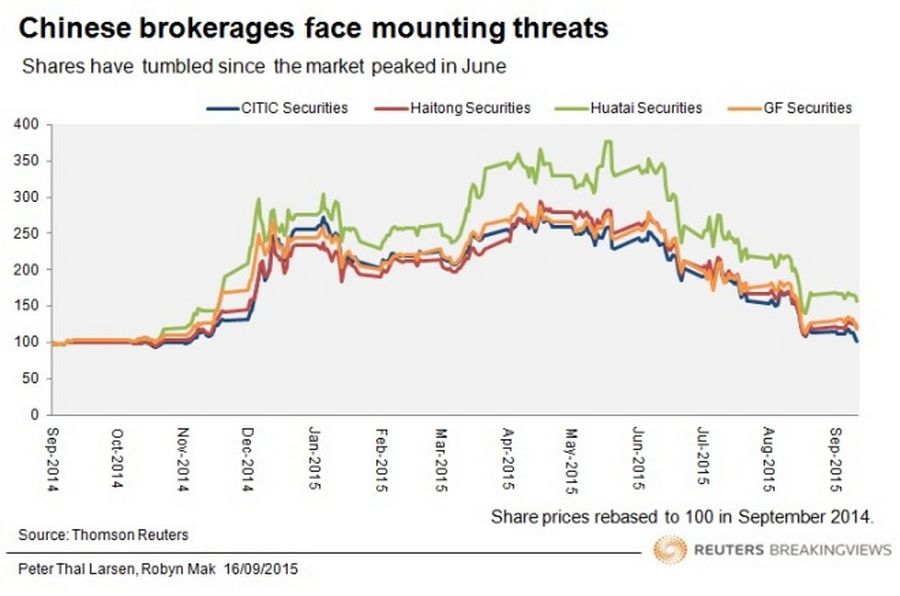

This grim picture is reflected in brokers’ own share prices. CITIC Securities’ market value has dipped below $25 billion – roughly $40 billion less than at its peak in April. The company is now worth little more than the book value of its equity, below the average for the last five years. Even if the insider trading allegations turn out to be exaggerated, China’s securities firms face a long struggle to regain their swagger.