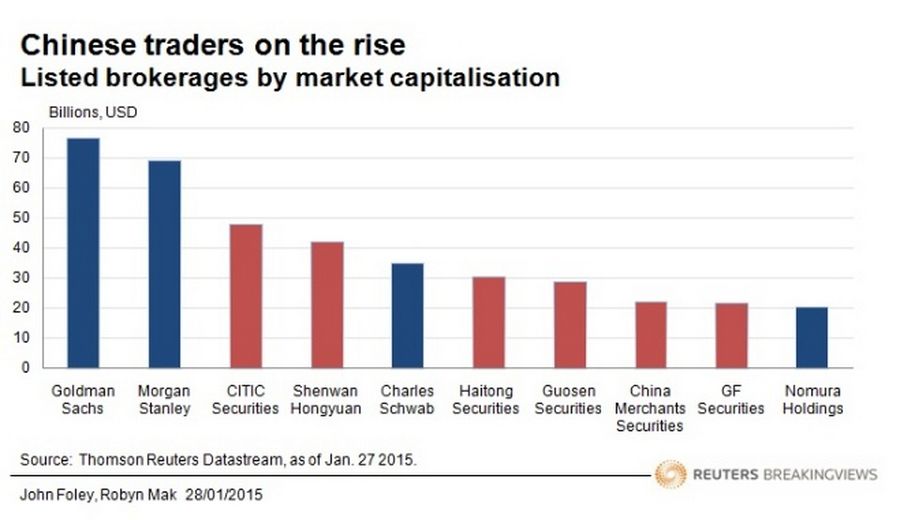

It’s hard to think of a better embodiment of China’s soaring stock market than Shenwan Hongyuan. Shares in the brokerage - newly formed from the merger of China’s tenth and sixteenth biggest trading houses - reached a valuation of $47 billion on its first day of trading. That made it bigger than U.S. brokerage Charles Schwab, and a fitting emblem of political investment mania.

China’s securities houses are surfing a wave of investor exuberance. The listed ones trade at a median 49 times this year’s expected earnings, according to Eikon, more than triple the global peer group. The excitement is mostly confined to the mainland. Haitong Securities’ Shanghai-listed shares cost 49 percent more than the equivalent in Hong Kong. Back in October they were worth roughly the same.

Brokerages benefit when stock markets rise. But the growth of margin trading, where investors leverage bets by borrowing against their shares, has created something of an Indian rope trick. Brokers charge fees of around 8.5 percent on the amount they lend – creating a much more attractive spread than banks get on their loans. Margin credit is around 3 percent of the Shanghai market’s value – more than the New York Stock Exchange. Even regulatory curbs haven’t turned the tide.

There is a genuine case for ebullience. Money effectively trapped in the People’s Republic by capital controls has to go somewhere. Even after the recent spurt, the annualised gain in the Shanghai Composite Index since 2010 is just 2 percent – far behind China’s economic growth over that period. Shanghai stocks trade at an average multiple of 14.5 times historical earnings – hardly stretched by international standards.

Underpinning the boom, though, is a dangerous belief: that the rally can be sustained by political will. As growth slows and industrial profits slide, a roaring market looks increasingly incongruous. It’s true that if stocks were to collapse, many middle-class individuals would feel distinctly less content – an outcome that politicians would like to avoid. But frequent attempts to reverse a bear market didn’t work in the past. There’s no reason to think they would now.